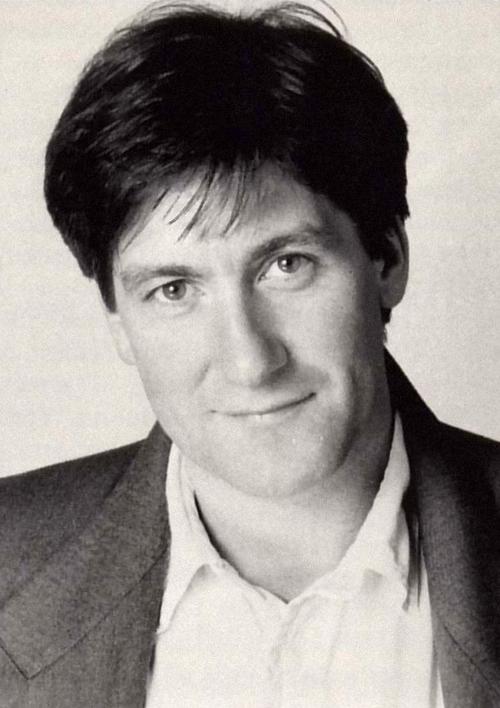

An Interview with George Fenton by David Stoner

Originally published in CinemaScore #15, 1986/1987

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor and publisher Randall D. Larson

Three major projects from British film and television in 1984 brought the name of George Fenton very much into the limelight of film composition. These were the mammoth television adaptation of THE JEWEL IN THE CROWN, Richard Attenborough’s award-laden GANDHI and Neil Jordan’s extraordinarily poetic THE COMPANY OF WOLVES.

Born in 1948, Fenton learned to play the guitar at eight and the piano by the time he was thirteen. He was educated at Oxford, taking organ lessons and subsequently studying ethnic music with Janos Leahar. He began his musical career playing guitar as a free-lance session player for recordings, theatre, opera and ballet. In addition, he played a wide range of middle-Eastern and far-Eastern instruments and one of his recording jobs in this capacity was for the musical score to The Man Who Would Be King. In 1968, Fenton was the featured guitarist and played the character of Tredgold in the West End production of Alan Bennett’s 40 Years On. The music director on this was Carl Davis and the two became close friends as well as collaborators. The following year saw the release of We Were Happy There, a concept album along the lines, and a continuation of, 40 Years On, with music by Davis and lyrics by Fenton under his real name of George Howe (it was changed to Fenton since, as a performer in 40 Years On, there was already a George Howe registered with Actor’s Equity).

His early film credits were for songs only but it was his work in theatre since 1974 that got him real attention. Through the help of theatre director Peter Gill, this led to television and film work, although he still spends much of his time scoring for the theatre.

This interview took place shortly after the English album release of THE COMPANY OF WOLVES at the composer’s home in Chiswick, London. He shortly thereafter completed the music and songs for BILLY THE KID AND THE GREEN BAIZE VAMPIRE, a new British film that mixes vampires and competitive snooker! His latest score is 84 CHARING CROSS ROAD.

How did you become involved with COMPANY OF WOLVES?

I was phoned in January [1984] by Chris Brown, the producer, who I’ve known because we went to school together. There was another project that he was doing as line producer, which I was going to do at one point but was unable to. But it did allow us make contact again. So he rang me up and said “Look, I’d like to send you this script, would you like do read it? Neil Jordan’s the director and he wants to meet you nd talk to you about the music.” So I don’t know whose idea it was that I should do the film but I do know that Neil saw WALTER and liked that very much. They came round to see me and there were two bits of music needed in the actual shooting of the film, the village wedding and the marquis scene, so I started then and found music. Both bits were eventually used thematically in the film, though I didn’t think of them in that way at first.

How did you become involved with COMPANY OF WOLVES?: It was just source music at that time?

Yes. I found those things and subsequently went to see the rushes much earlier than I normally do. Then came the rough cut. They changed the cut constantly, almost up until I started scoring and even up until I started recording. Although there were only three weeks in which to score the film, I’d had most of the ideas by the time it came to record. The thing is, there is a tremendous amount of music and therefore there is a lot of pressure to get the thing done. It’s quite considerable, but really when people say that there’s no time or never enough time for composers I think it’s more to do with the fact that you have to react immediately and you have to set up your idea of how to score it very quickly. You see the film and you react to the film.

Do you like being involved with a film early on?

The advantage of being involved early is that you get to know the people. They aren’t always particularly forthcoming about things like music because they don’t feel they have the necessary language to talk about music that coherently. The reason in getting involved early is that they can say something and have the confidence that you understand what they mean. You can develop a language based on other people’s work that you mutually admire and why you admire it. You have to evolve a working relationship in a short space of time. The trouble is that they don’t know what they’re going to get until they actually hear it.

How closely did you work with Neil Jordan on COMPANY OF WOLVES?

Very closely. Because I’d decided to write a score for electronic music in particular, I was able to do examples of certain sections of the score quite early on and then take them into the cutting room and say, “well, what do you think of this?” Of course that takes a tremendous amount of pressure off the composer because once you establish that what you’re doing is right and they like it, then you don’t have this terrible thing of piles of paper building up in the tray beside you and it all hanging on the recording and maybe you’re going down the wrong road. It’s a terrible feeling. By taking he pressure off, in a way it makes you freer in thinking. You feel more relaxed. From that point of view as well as every other point of view it was a really happy experience. So I worked closely with Neil in that sense because I could always show him something. He’s very responsive to people’s original thought. If you say, “well, I would like to try this or have you heard this or what if the church bell sounded like this instead of a real church bell or whatever…” He kind of harnesses all that. He has such a strong overall vision of the film all the time. Really stimulating to work with.

Are you happy with the way the music has turned out?

I have reservations about the way the music has turned out, but then one always does have reservations about such things. I hope there never is a job that I could turn around at the end of and say “that’s it, I could never do any better than that.” There’s always something where you think, “maybe I could have done it better this way or that way.” I think the score reflects Neil’s image of what the score should have been. At least, it’s in step with his image of the film. From that point of view I’m pleased. Also I’m pleased because it’s got a sound of it’s own.

I think it’s going to open a lot of people’s ears to George Fenton, the composer. After SHOESTRING, BERGERAC and JEWEL IN THE CROWN, this is going to be something they weren’t expecting.

I hope it does. It’s one of the things that success does. For example, John Williams is an incredibly successful composer. If you heard an album and it was like COMPANY OF WOLVES, you would say “Good Heavens, I didn’t know he does things like that,” and similarly if you were to hear an album by Vangelis that sounded like John Williams you would go “Good Lord”, do you see what I mean? That is the price you pay for having tremendous success. If your music has terrific success away from the film then, although the rewards for that are considerable, there is the problem that you have become known for that music. The great attraction of writing film music as a way of writing music is that you get tremendous variety. So it’s almost inevitable that despite the things you’re known for, if you carry on writing, you’re going to surprise people. You have to write differently and yet it’s only the music that is known outside of the film that people generally remember you for, and you can’t expect that everything you do will be equally well known. I would much prefer if people knew my music outside of anything it was for, something like this film, as opposed to a signature tune.

This was a tremendous challenge. Also, although I’ve worked for years and years with synthesizers, it was a tremendous eye-opener from the point of view of the capabilities of electronics and the potential of mixing.

It’s not an obvious electronic score. There are sounds that you realize can only have been made by electronics, but they fit in very well with the orchestral score.

Yes, I’m more interested in that grey area between sound and music where one stops and the other starts. To be honest, that turns me on more than anything else other than melody. That’s the most fascinating and unknown area in music.

‘The Boy and he Devil’ is a particularly eerie track from the film.

Well, that’s a classic example of the use of the modern synthesizer. The fact that you can sample real sounds (in that case it was me breathing) and treat it, drop it in pitch and mix it with a solo bass, you know, things that are so outrageous. The music was specifically written to be recorded rather than performed. That’s an important feature of the music. It would be impossible to play that live. That is not to say that it is not a musical work. It’s just to say that in thinking about it, I made certain assumptions in recording technique.

The reason why people tell you to use several bass flutes, for example, if you’re going to play a tune, is because they play so quietly; whereas in fact I didn’t use three bass flutes to play one line, I used three bass flutes to play three different lines because the perspective is endlessly variable and it’s particularly variable if you have isolated digital sounds that you can get from three computerized synthesizers. Using three bass flutes and three solo double basses leaves you with space in the overall sound. It’s an extraordinary idea for a score, in a way, but it seems to me that it doesn’t sound unnatural. It seems in keeping with the rest of the score.

One of the things that music does is make you feel safe. You think, “Oh, I know where I am now. This music is telling me this or that.” But on this film, and the reason it was such a challenge was because I didn’t want the music to tell you anything that you didn’t already know.

The film keeps you off your guard all the way through.

Yes. Also, and I don’t know if I’m responsible for it, but I hope I am a little bit, is that you don’t know what kind of film it is. Except in the middle story with the girl in the village with her parents, where I made a deliberate decision. I felt it should have something of the old Hollywood storybook quality about it, which is why, for instance, when she walks through the forest with her Granny, the forest sort of talks. I did that with orchestral instruments deliberately to maintain the more conventional musical world of her dream rather than the story within the dream. I did several schematic things that I normally wouldn’t do with a film because it seemed to me that one had to be careful not to upset the ambiguities there. You had to make sure you followed it quite closely, otherwise you tend to blur the film instead of heightening it.

It’s not the sort of film where you can go in with a conventional horror score.

I’m not sure I know what a conventional horror score is.

Something like Goldsmith’s POLTERGEIST, perhaps, where he had little option but to go in with all guns blazing.

Yes, that’s true. It’s interesting you should mention him, because, going back to what we were talking about earlier, success away from the film, there is a classic example of somebody, although he has tremendous success with his music, who has not had one commercial success away from the film or as a result of one film and yet he has to be the most marketable film composer in the world. You can think of loads of scores that he’s done that have been good, but they’re all quite different.

It’s amazing that Goldsmith didn’t win an Oscar for UNDER FIRE.

Ah, yes. Well, you see, it’s one of those things. There is probably a voting reason which is to do with the fact that the Academy in America works the reverse of our Academy here. In England, the membership nominates and a panel of so called experts, vote. At least they’re conscienscious and they just view what they’re given. They are impartial in that context.

In America, the panel nominates, and then they put it out to the membership, which is why they say in America that getting a nomination is as good as winning. Well, if you put a film out to the membership that’s why you get this tremendous run on a film, like GANDHI, for example. They’re chosen by the hierarchy of the Academy and they nominate and one has to assume it’s impartial, but once it goes out to the popular vote, it’s bound to be reflected in the generally popular appeal of things as opposed to being judged purely on the excellence of its contribution to the film.

I’m not so much talking about myself because I would have been highly embarrassed if GANDHI had won the music Oscar as opposed to E.T. because of that reason. That score was a worldwide smash. CHARIOTS OF FIRE, for instance, was nominated here but didn’t win. But it won in the States. Yet if it had been down to the membership in the British Academy, I would think it would have undoubtedly won. Because it was judged on he parameters that they set, you find yourself judging it on things other than the popularity of the music.

Tell us about GANDHI. You have an interest in Eastern music and instruments. Did that play any part in your being offered the film?

Not really. GANDHI is like a fairy story. I got a phone call at my agent’s asking if I would call Michael Attenborough, the theatre director. I rang up and he said “I’ve heard all your work in the theatre, particularly at Riverside Studios in Hammersmith. My father is doing this film about Gandhi and I think he should hear your music.” I thought it sounded like a gag, it was so ridiculous. I said “If you really want to, but I’m sure he’s got other people in mind.” He said, “No, I’d just like to play him a tape of your music.” He came round, made a tape of some music and told me to write a letter to his father. So I wrote this letter saying “Here I am, here’s my music.” He took it away and then I didn’t hear anything from him for about four months.

I had never even entertained the idea anyway, and had completely forgotten about it. Then I got a phone call from Richard Attenborough’s office and I went to see him. He said, “I just wanted to meet you because Michael’s told me about your music in the theatre and I’ve heard the tape but I think I should tell you that we’re very close to making a deal with another composer to do the film.” So I said “Oh well, nice to meet you” and so on, you know, the usual thing, and I went away.

I went on holiday for two weeks and I got a telegram saying that this other person was definitely going to do the film and that was that. So then I came back and there was a call saying that Richard Attenborough had rung. I called him up and he said that it had all fallen through with the other person and did I want to see the film? I went to see it on a Wednesday and that Saturday they put me on a plane to Bombay and that’s literally how it was.

I think how it happened was that for years he’d been trying to set up this film using people like Alec Guinness, Dustin Hoffman, and he ended up with Ben Kingsley. I think the person who suggested Kingsley was Michael Attenborough. Possibly because of that, he chose me, because I know for a fact that there were feelers out from all of the big Hollywood composers. The only other thing in my favor was the fact that because I was young and because I do specialize in Middle-Eastern music and had a nodding acquaintance with Indian music, it meant that it would be easier for a working relationship with Ravi Shankar than it would have been for a person of equal eminence. Who knows? All I do know is that it was a fantastic chance. A wonderful time.

How long did you stay in Bombay?

I went twice for two weeks each time.

At what stage was the film at?

It was almost fine cut when I first saw it. Really, the first time I went out there was to meet with Ravi Shankar to see if he was prepared to work with me. The second time was to actually write the thematic basis for the score which we did between us; not the orchestral bits at the beginning, but the main body of the film. Then with the notes I had both on tape and written down from our conversations, I came back and wrote the score.

It wasn’t a case of his doing his sections while you did yours?

No. We worked together. There were certain things he didn’t do, like the military band stuff. And most of the music in the South Africa sequence I did because it’s purely orchestral. Certain things, like the train journey, he did without my having anything to do with it. In the mixing, because of my availability, I was in the studio much more than he was. From that point of view, I had to conduct, produce and musically direct all the music just because I was an easier person to liase with in the control room than he was. Also, all the time I’d been doing the film, I’d been in and out of the cutting rooms and I was much more the “jobbing” composer. They’d say “we need a bit of music here.” Then I’d relay these thoughts back to him and we’d decide what to do. It was very tricky to do GANDHI. Ravi Shankar couldn’t have been easier to work with in the sense that he is known for the fact that he has pushed back the boundaries of Indian music. He’s experimented quite a lot. On the other hand, when I came back and wrote the score and they came over and I tried to teach the soloists the parts, there were several pieces where he said “Oh, no, you just can’t do that.” I said “Well, I can’t have the orchestra just playing a unison D the whole way through the film.” He said, “But if you change the piece, it changes the raga.” I said, “Does it matter if it changes the raga?” It was a kind of win-a-few, lose-a-few situation. Some of the time it did matter if it changed the raga.

You see, the whole thing with Indian music is that it’s a case of the language of Indian music being the language of the Indian people. They’re nearly all musically literate. They recognize a raga like we recognize “God Save the Queen.” [Raga is a Hindi term and is the approximate equivalent in Indian music of a scale, but it refers more widely to a piece of music which has a raga as its basis and whose mood or atmosphere is determined by the repeated use of certain notes of that raga. – ed]. There are certain ragas that are associated with certain times of the day, or certain seasons or romance, and so you have to be a bit careful unless you’re going to alienate the Indian audience. Not only in India but worldwide, so from that point of view it would have been absolutely impossible to score GANDHI without his overseeing eye and his contribution of that knowledge.

Was it always intended that Ravi Shankar would score it with another composer?

I think he would have had to because he doesn’t write. I mean, anybody who is musically literate could write a score if he were to dictate one. Orchestral music is vertical music. It’s to do with what happens to the relationships between all the instruments at that point in time. That’s what a western score looks like. There are lines that people follow, but, basically, and particularly film music, it’s nearly all vertical proposition. That really isn’t the right word, but the point is, Indian music doesn’t have any vertical. It’s only line and rhythm.

I’m pleased to say that I managed to persuade Richard Attenborough that there was a future in trying to incorporate Western and Eastern music together. There is an area where the two can work together in the same piece of music. He’d always envisaged having a Western composer doing the Western bits and an Indian composer doing the Eastern bits.

I think also that when you see the film you realize that it isn’t really an epic. He’d always lived with the film as an epic idea and when he finally arrived at the final cut, a great deal of the film is just about one man and therefore it wasn’t an epic film any more. There wasn’t really a great deal of hanging around on “great big scenes.” They tended to come and go, but basically you went straight back to the man. It was an epic subject and it’s a fantastic film, but it was no longer an epic film from a scoring proposition.

You scored THE JEWEL IN THE CROWN. Did the success of GANDHI have anything to do with your being asked to do that?

GANDHI didn’t have anything to do with it because I was asked to do JEWEL IN THE CROWN before I did GANDHI, and I was asked to do JEWEL because of my work in the theatre. Christopher Morahan, the producer of the series, is a director at the National Theatre and I’d done some work there. Somebody at the National had said to him that I might be a good person to do that because I’ve done a lot of ethnic music and was interested in that sort of thing. So I suppose I was a person he vaguely had some contact with in the theatre sense but also that I was used to the disciplines of writing for film. I’m not really sure why he asked me but he did ask me before they went and shot it. But it was a year and a half before I started work on it, which is very unusual. Nevertheless, I had to do a lot less work on it research-wise because I had done GANDHI.

Did JEWEL present any special problems because of its length?

I would say that JEWEL was largely problem-free. Actually, that’s not really true. The thing about JEWEL is that it’s highly narrative. Also, the fact that it is in India is by-the-way. It’s about the people and it just happens that the inter-relationship of those people is all tied up with their being in India and also where they are historically. Beyond that, there’s nothing particular in the equation that is special to India.

The music for the series was what I call a real “slow burn.” There wasn’t one theme that just came out all the time. The front titles were different to the end titles and the theme in the front titles was only quoted once in the first episode and then came through more in the third episode. The love theme found its way in but I think by the end of the series it was thematic.

The series stretched me, but in a totally positive way. It didn’t panic me in the way certain things can when you don’t know how on earth you’re going to do it. It stretched me in a way that I thoroughly enjoyed. I loved doing all the empire-type music. It’s such an enviable thing for somebody to say “how would you like to write something like Elgar?” Not that they said exactly that, but we did have a conversation and the end of it was that maybe it should be something like that. But to be finally faced with that and you write something that sounds like Elgar and English and you can have the finest orchestra you can lay your hands on to play it!

The problem with doing JEWEL was that you couldn’t pin it down to one theme. It would be impossible and also desperately inappropriate to give the series a thematic common denominator whereas something like BRIDESHEAD REVISITED needed it. BRIDESHEAD was a much bigger experience than the book, but JEWEL was not much bigger than The Raj Quartet. You don’t need to blow up The Raj Quartet in that sense, it’s already a massive work and it’s not difficult to think in terms of thematic common denominators.

It would have been possible to write something that would be instantly recognizable and popular and sold a lot of albums, but it wouldn’t have worked for the series.

Yes. It’s a moot point. You could say, to be perfectly selfish about it, here is an opportunity to write a theme that everyone will know. I think there is tremendous value in that, don’t misunderstand me. I’m not saying that I think it’s a bad thing to do because it does, without doubt, make people remember the show. That’s great, but I think that that is a different audience and and different kind of audience reaction than the people who made JEWEL were looking for.

I do firmly believe that film music only exists for one reason, and that is to serve the film. I thought that when I was first faces with JEWEL, the one thing there should be is an opening and closing which is the same because, after all, it’s just like bookends. It’s saying “Settle down, here’s JEWEL IN THE CROWN…” and “…that was JEWEL IN THE CROWN, don’t forget to turn on next week.” But because the producer and two directors decided (which was quite a late decision since it was a long time after I’d scored the first two episodes) that the front titles were going to be newsreel film depicting the last days of the Raj, and it became impossible to do what I’d wanted.

The film takes place at least 30 to 40 or more years earlier and what it’s showing you is where the ethic came from that governs these people. Pomp and circumstance, that kind of thing. But every time you came to the end of each program, it was actually taking that apart. Therefore, I think it would have been possible to use the music at the end of each episode at the beginning and it would have been truthful to the series, but there is no way that, at the end of each episode you could then put the Elgarian march again because it would have been wrong. It would just seem to be cynical.

Of course my own cynical view is that if you haven’t got them by the time the credits roll at the end you can forget it anyway so what does it matter what you play? I mean, that’s what I think as a viewer. At the same time, I admire their integrity in making that kind of calibre of program where you actually take the responsibility for your audience right up until the last credit rolls and what frame of mind they should approach next week’s episode.

It might not be something you consciously think about but over the period of the series you do appreciate that you’ve got people here presenting something and actually caring about the product which enhances the enjoyment.

I think so. You don’t feel you’re being hyped. I can tell you that an incredible amount of care went into it from everybody’s point of view. I slightly overdosed on Indian music as a result of doing GANDHI and JEWEL. I thought if I had to anything else where I’ve got a droning fifth in the bass, I don’t know what I’ll do! I became numbed by it in the end, but I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Of the three media, theatre, film and television, which would you say you were happiest in?

I feel the most relaxed in television.

Because of the smaller scale?

No, it’s not because of that. I mean, the orchestra I had for JEWEL IN THE CROWN was bigger than that for COMPANY OF WOLVES and the orchestra for BLOODY KIDS was bigger than that for GANDHI, and so on. It’s not so much the scale, it’s because the kind of feeling behind making a television program doesn’t have the same conecntration of energy and therefore pressure that you get when you’re aiming for a theatrical performance whether it be for theatre or cinema. The only thing about the theatre which is different is that frequently you’re writing for live musicians to play every night and therefore you can’t take nearly as many liberties in the theatre as you can when you’re recording.

I think there’s something inside you which stops you from writing anything particularly difficult if you know it’s going to be played live every night. You have the interests of the people playing it in mind as well as the people listening to it. You know the effect of a good performance on people listening to it is governed by the interests of the people playing it. On a film session, you’re only asking for three hours of commitment and you don’t have to worry about that. There’s a certain thing called “green energy” which is what motivates them if nothing else, although I suppose that is rather cynical. But you get the very best players and they play tremendously well but they also are highly paid for it and it’s a one-off, so you can ask them to do very odd things or things that are very dull for them to do but are very effective in the overall picture. You have much more control over the sound that they give you and so on. You kind of write in a different way. Plus, if they get it wrong you just go again so you can get them to do very complicated things.

Plus, if they get it wrong you just go again so you can get them to do very complicated things.

What do you consider to be influences on your work?

It’s a pretty eclectic list, really. Because I have been exposed to a lot of different types of music without being totally conscious of it. In broad terms, I’d say that I’m influenced, for one thing, by church music. But influenced by church music in a dramatic sense; not by baroque music in any sense of form, but by the drama of church music. That’s to do with the fact that I studied the organ so I know a lot of organ music and what goes with it, which is choral music. I don’t know quite how those influences show themselves – I mean, how can I say that I’m influenced by Bach when hardly anything I write sounds like Bach – but they do. I’m frequently conscious of things in my work that emerge and turn out to be that. Even hymns.

The other influences that are, in broad terms, like that are, for want of a better term, “hooligan” influences. That is to say, rock and roll, which again, if you listen to something like COMPANY OF WOLVES, where does rock and roll figure in that? But it just does. Whether it has to do with rhythmic things that I do, or whatever, but it definitely has an influence and that’s where I’m most at home, with rhythm sections.

In my own area, I think I’m influenced by Bernard Herrmann and I know I have been by Ennio Morricone.

Any particular Morricone scores?

No. I’ve just listened to loads and loads of his scores and I think he’s just so bold. I feel rather reserved as a character and hearing Morricone’s scores unlocked a bit of me. I mean, I don’t think I write music like he does, but it just affected me, a kind of “go for that and be strong” sort of thing. I’m often surprised how vicious or how aggressive my music can sound or how sad and dark it can be

I’m interested in your general approach to your work. What do you feel between seeing the film at whatever stage the cut is at, and what do you feel when you’re sitting in a cinema watching the film knowing that you can’t go back and change anything whereas you can change concert and theatre pieces.

It’s probably for that reason that I don’t very often go and see things that I’ve done.

There is also also the fact that with film, and occasionally television, more people are going to hear your music. You must be aware of something like that.

I try not to be. When you’re lonely and exhausted and struggling away in the middle of the night scratching out another cue, you’re bound to think about that and everybody solves it in a different way. In my view, there is only one person who makes the film and that is the director. Now, of course, people will leap up and say, “well, frequently the director just shoots it and the producer makes it,” but what I’m saying is that at the heart of every film there is one person or maybe a team of people, and it actually is their film. My way of thinking about the effect or lack of effect in the score is just to concentrate on that one person and say “it’s their film and all I can try to do is to give them what they want for their film. If it’s what they want, they’ll be pleased to have it and if it’s not, then they’ll probably drop it.” It’s much easier to deal with psychologically if you just write for that person.

© David Stoner 1987/2018

Leave a comment